– The Kinstead – Vermont’s Shelter Home for Children

By Paul Heller

It started with a gift of seven acres of prime Montpelier real estate on Main Street hill. The citizens of Montpelier, aware of the need for a refuge for children in difficulty, donated the land for the Kinstead. The name suggests a home for children whose parents are unable, for one reason or another, to provide for them. Because foster care in families was not, in every case, an option, an alternative was needed. Lorenzo D’Agostino’s History of Public Welfare in Vermont described the unique mission of the Kinstead in 1948:

The State of Vermont has no state-managed and supported institution for dependent children who are normal. The state supported institutions are for children who are mentally deficient, physically ill, or delinquent. The one exception might be the Kinstead Home in Montpelier which houses about thirty dependent children. The original grant of 1921 stipulated that the money was to be used for a “shelter home where dependent, neglected, and delinquent children committed to the care and custody of the board of charities and probation may receive physical and mental examination and care before being placed in private family homes.”

The maximum stay for any child was estimated at ninety days.

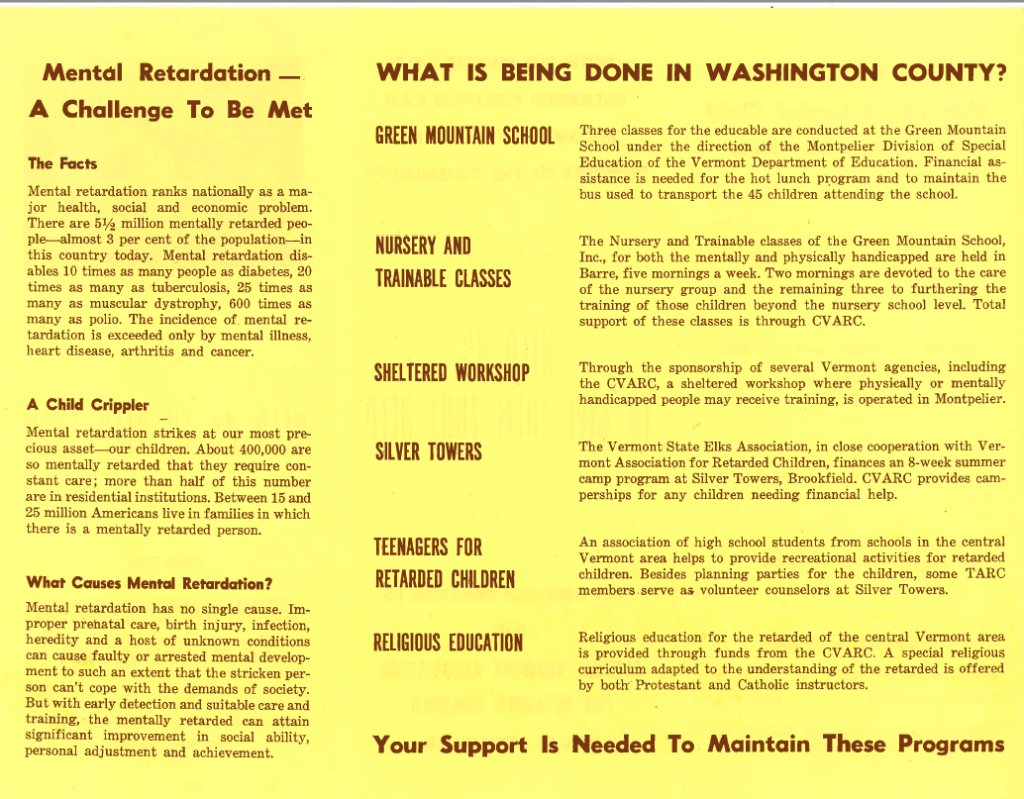

The October 30, 1947 “Golden Anniversary Edition” of the Argus states that “The Kinstead” means “home for our kin” and the name was intended to evoke a caring, family-like atmosphere. The first public announcement of the shelter appeared in late 1921 with an architect’s rendering of the facility. An announcement in the Boston Globe contained a brief description of the planned structure. “The home is named Kinstead. It is 72 feet long and contains a basement, two floors and an attic. The offices, reception, reading, game, dining rooms and kitchen are on the first floor and the girls and boys dormitories and matron’s room on the second floor.” In fact, the building was constructed pretty much as depicted in the plans and was expanded with the addition of a third floor years later. Walker and Walker of Montpelier were the architects.

Frank Walker, born in Williamstown in 1864, was a self-schooled engineer whose love of design left its stamp on the townscapes of Barre and Montpelier. Through the years he completed plans for important structures in central and northern Vermont: the Supreme Court Building on Montpelier’s State Street, the Town Hall in Stowe, two dormitories for Norwich University, and four school buildings in Barre, including the finely appointed Lincoln School. Walker left a legacy of countless residences and commercial buildings in central Vermont that bear his imprimatur and many have been standing long enough to have been repurposed at least once, including the Kinstead. By 1920 Walker had moved to Montpelier and established a successful dealership in coal and fuel oil. He died at his Elm Street home in 1950 and was buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Montpelier.

Even before the home for neglected children opened, the Rutland Herald evinced a suspicion of the new State enterprise.

It is understood that a large portion of the first cost of this shelter home has been borne by private contributions, but it is a fact that the state appropriated $15,000 therefore, in addition to $50,000 for the use of the state board of charities which has the shelter home in its charge. This is the way that new state institutions are born, first the small initial expense – mostly met by private funds – then a building or two, then more buildings, and finally, a full-fledged institution with a full-fledged staff and payroll, permanently attached to the state treasury. This is the plan of sob sisters of both sexes and all ages and under all conditions. Get a legislature interested in a worthy and appealing cause, get a small appropriation, get a building up, then turn the interesting infant over to the state to be loved, honored and cherished for the rest of its official life.

Penny-pinchers aside, the city and state were proud of their new and much-needed facility.

The official opening was on April 8, 1922, but two days earlier over 200 people attended a meeting at the Montpelier High School auditorium where Frederick Knight of Boston’s New England Home for Little Wanderers spoke on the care of “dependent and defective children.” At the grand opening of the Kinstead, William Jeffrey, Secretary of the Vermont Board of Charities and Probation and overall supervisor of the home received visitors. Jeffrey used the opportunity to thank the generous donors who contributed funds and equipment “to give Kinstead the atmosphere of a real home, to make it a place where the children could get their first start in right living under wholesome conditions.”

Unfortunately, in less than a year, Secretary Jeffrey would become the object of a secret investigation that was, for a time, a minor scandal in town. On January 3, 1923 he was accused of keeping employees on the payroll “when they were unfit for work” and “bagging food and carrying it home” on his visits to the facility. Although the Rutland Herald was early to characterize the shelter home as a potentially expensive whim of bleeding hearts in the legislature, it dismissed the suppressed investigation as a “Spinster Quarrel” about donuts. The “whole business” declared the Herald, “has been handled along lines that might naturally be expected from the inmates of an old ladies home.” Despite the insulting language, the newspapers described the disagreement in detail.

Edna Jackman and Mira Tibbets had been provisionally employed to facilitate the day to day operations of the Kinstead when it first opened. They had previous experience running a similar home elsewhere. Jeffrey then hired an overseer for the shelter home, Mrs. C.H. Dana, and there was immediate friction between Dana and the staff. To complicate matters, Mrs. Dana was the wife of Vermont Senator Dana, who was employed by the Board of Charities. According to the Herald, Jackman and Tibbets claimed that Mrs. Dana used to “cuss around considerably, using language unfit for tender ears, that she was quarrelsome and unfit for the custody of the kiddies. Then they were told that if they couldn’t get along with Mrs. Dana, they knew what they could do. Get out. Evidently Jeffrey fired the wrong parties because the spinsters promptly went “down the line” with a general bawling out of the Kinstead management that got the institution “in Dutch” with the Montpelier people who had done a great deal to get the home started.”

Following the complaint an investigation was ordered which, after being read to the Board of Charities, was for some reason kept secret. It was later revealed that the report criticized Jeffrey’s financial management of the Kinstead and suggested that the fire in the furnace was allowed to get so hot that the safety of the children was put in jeopardy. Perhaps more damning was the fact that Jeffrey waited too long to remove Mrs. Dana from her supervisory role and, for some reason, her husband was still on the payroll of the institution. But there was also testimony that contradicted the allegations of impropriety, and Mr. Jeffrey in particular, according to the Boston Globe, “positively denied the charge which stated that he had hesitated to permit the adoption of a child at Kinstead for the reason that $2 a week was being paid to the home by the city of Burlington for the support of a child.” The findings of the investigation were not acted upon.

After this somewhat rocky start, the home was put on an even keel with the arrival of Anne Griffin in 1926 and, under the direction of the Commissioner of Welfare, John Weeks. She served as Matron for the next thirty years. Under her tenure the home was remodeled and expanded and became more than a temporary shelter to serve the needs of hundreds of Vermont children who, for one reason or another, found themselves in need of the Kinstead’s services. During the years Griffin held the office of Matron, according to the Free Press, ”with only the help of a day worker to assist with cleaning and other household chores, she has tended the wants of as many as 47 children at one time.”

When, in 1955, Anne Griffin was forced to leave at the mandatory retirement age of 70, the home reverted, once again, to a temporary shelter. For various reasons, including the development of a more robust system for public welfare, the population of the Kinstead dropped dramatically. By 1960 the state realized significant savings by closing the home and placing the dwindling population of children in foster homes. For a few years, the former shelter home became the campus for the Green Mountain Special School which served developmentally disabled children, but as education trended toward mainstreaming special-needs students, the facility found itself turned over to other uses. Finally in private hands, it became headquarters for the New England Culinary Institute. The building saw sufficient remodeling and hosted administration, classrooms, dormitory facilities and a banquet room for the cooking school. Today, the old orphanage houses counseling offices and an herbal healing facility. While various proposals to develop the 5 plus acre site have been discussed, none have pending status with Montpelier’s zoning office.